Never.

That’s how often you should read the comment section on a parenting blog. This is probably true at the best of times, but I think we can all agree, these are not the best of times.

Like a lot of parents, I’ve recently been navigating being at home with three kids in different grades. I’ve been clapping out syllables with my 10 year old, assisting my 12 year old with multiplying and dividing fractions, and instructing my 6 year old in the proper way to hold his pencil (in spite of the fact that I never learned to correct my grip). I’m signing into multiple Google classrooms, Freshgrade, Epic, ReadTheory, Razkids, Newzella and Zearn accounts (yes, those are all real). Not to mention multiple Zoom conferences. I’m also trying to bake bread, make crafts, facilitate my kids reaching out to friends, get outside and limit screen time.

All while working and trying to keep myself and my family safe from a pandemic.

Like a lot of parents, this is all new. Unlike a lot of parents, I’m not also attempting to manage working from home. But even the little writing and projects I attempt are punctuated by interruptions, questions, requests for snacks, and complaints of being tired and bored.

Some days it all works really well. You see a new concept begin to make sense to your child. You cherish the time at home and the conversations that arise naturally. Siblings play well together. The bread rises, and you take turns punching it down together.

Other days are significantly harder. Days when you spend hours doing schoolwork with little to show for it. When you explain the concept of equivalent fractions with numbers, words, pictures and physical objects and it still doesn’t hit home. When the novelty of crafts and baking has worn off completely. When you are only going through the motions of normality, and your children know it.

Recently a writer composed an article sharing her experience of one of these tiring days at home with her child. It was honest, it was vulnerable, and it didn’t paint her in the best possible light.

She was destroyed in the comments section.

Some readers attacked her for complaining about a life marked by privilege. Some patted themselves on the back for their superior upbringing and parenting, taking the opportunity to showcase the ways they have managed this crisis so far. Some derided the writer for allowing her child to become spoiled and run the household. Another chided the writer for writing about a concept so obvious: “Of course parenting is hard!”, they scold.

What was universal among so many responses was a complete lack of empathy. Each respondent unable or unwilling to imagine a scenario different from their own. Unable to listen to another’s grief and frustration without expressing judgement. Even those attempting to contribute helpful parenting advice (dangerous, that) came from a place apart, above. Very few seemed willing to accept her vulnerability and meet her in the midst of failure.

Of course, no one is surprised by this story. For the longest time, competition, individuality and self sufficiency have been given much higher stature than seemingly ‘soft’ virtues such as empathy and compassion. The unspoken message has been that seeing another’s perspective is nice and good, but inessential. People displaying their vulnerability is uncomfortable, and expecting empathy and compassion from strangers is naive and idealistic.

But that is exactly what we are depending on right now. The empathy and compassion of strangers. A deficit of empathy affects more than just the comment section of a struggling parent’s blog. It needlessly puts others at risk and prolongs this crisis.

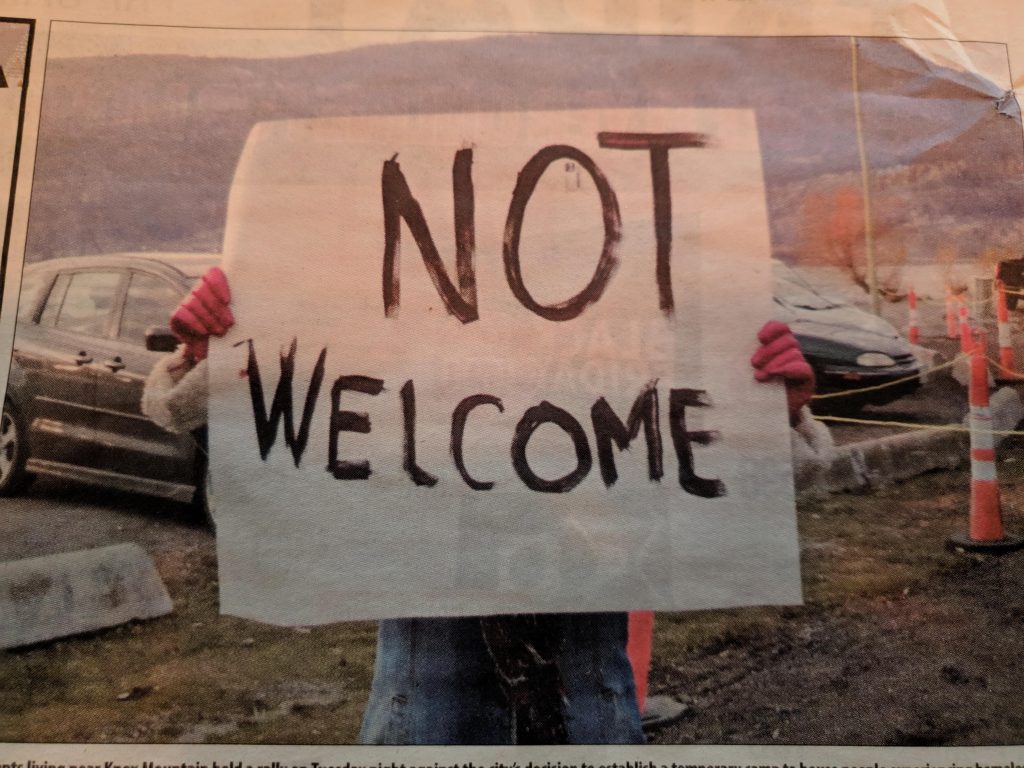

This pandemic has been marked by a deficit of empathy. Fistfights over toilet paper and sanitizer. Customers emptying entire meat sections. People stealing boxes of respirator masks from hospitals. People throwing their used and possibly contaminated gloves (and various other litter) on the ground next to shopping carts for others to risk picking up. As a society, we are seeing both the best and worst of each other during this crisis.

Now we find ourselves faced with a crisis that the individual is incapable of addressing. Suddenly, we are being asked to see ourselves as a whole. To do our part, and trust that others will do the same. To consider those weaker or more at risk than ourselves. As cases continue to rise, we will realize how linked each member of our community is to our own health and wellbeing. We just can’t see it yet.

Without empathy, the individual can’t see the big picture; can’t see beyond their own risk and discomfort. And as more and more individuals deem their risk of infection to be low or of little consequence (whether this is true or not), concessions begin to be made. That means decreased vigilance around physical distancing. That means more people meeting together. And that ultimately means the spread of this virus and the prolonging of our collective isolation.

I don’t say this to shame anyone. We’ve all seen an influx of self appointed ‘social isolating police’ pop up online. There is a thin line between reminding people of best practices and social shaming, and it gets traversed daily. We are all making decisions about how to best navigate this crisis with acceptable risk. Some of us are making concessions out of exhaustion, for productivity, for childcare, for mental sanity.

But empathy asks whether we would we make all of those same concessions if we were immunocompromised? If we had an underlying lung condition? If our health and safety depended on the vigilance of others?

I know from conversations with those most at risk that they have not reduced their vigilance. That our collective concessions are terrifying. They can’t afford to pretend that this virus is a hoax, or a government conspiracy, or overblown. They watch the increasing numbers in our province with an eye on how each infection increases their risk. Denial is not a coping mechanism available to them. To them, denial is deadly.

When I take a risk that is manageable to me, but not to someone else, it is a failure of empathy. That I cannot, or will not see from another’s perspective.

Perhaps we can begin by admitting that we have a deficit of empathy. That we have devalued virtues which are needed more than ever now. That more is required than what we have previously given. That in the face of threat, we have focused mostly on our individual needs and fears. And that in our conceived scarcity, we have become less generous, even with our concern for others.

As is often the case, we do not know where we are weakest until we are tested. And this is our test. To find the ways to see this crisis through more than just our small perspective. To expand our imagination, our consideration, and our compassion.

It has been said that we will get through this together.

This is true. But how we get through it, and who we are together, will depend greatly on our empathy.